Science and good practice must go hand in hand if we are to confront today’s most pressing challenges. This is the opinion of Anwar Fazal, activist from Malaysia and recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, also known as the Alternative Nobel Prize. Fazal speaks here as well as at the anniversary conference in Bonn about the importance of pioneering initiatives.

Science and good practice must go hand in hand if we are to confront today’s most pressing challenges. This is the opinion of Anwar Fazal, activist from Malaysia and recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, also known as the Alternative Nobel Prize. Fazal speaks here as well as at the anniversary conference in Bonn about the importance of pioneering initiatives.

In Bonn you will be speaking about the challenges of the 21st century. What are they?

Our biggest problems have already been described by Mahatma Gandhi as the seven social sins of the modern world: Politics without principles, knowledge without character, science without humanity and business without morals. I would add a few of my own: Rights without responsibilities, development without sustainability and laws without justice. Our society is at a tipping point, and the stakes are high. We are heading down a path of ecological suicide. Our economic system operates like a casino and our justice system favours just one percent of society, i.e. large corporations and the financial system. That needs to change.

How can education and science help?

Universities can become active on three different platforms: Teaching, research and – one that is too often forgotten – community engagement. There could be regular discussions with leading thinkers who challenge the current systems – systems that are only leading us from one disaster to the next. Discussions like these happen, for example, at Right Livelihood Colleges. These are places where young researchers and academics come into regular contact with Alternative Noble laureates. Research is infused with life experience and committed activists become involved in research activities.

Are there still too many researchers in the Ivory Tower?

The academic world could be much more influential than it is now. Academics need to engage more in what we at the Right Livelihood College call the five sparks of change: Supporting projects of hope, finding solutions, honouring courage, walking the talk and realizing the impossible.

How can the academic community be motivated to become a more involved in social change?

At the Right Livelihood College, we provide fellowships to Master’s and PhD students around the world who are interested in exploring the work of one or more of the Alternative Nobel Prize laureates. One doctoral candidate is doing research on migrant workers – one of the most difficult global issues right now – at the Center for Development Research (ZEF) in Bonn and at the Universtiy Sains Malaysia. She is receiving support from the DAAD. We hope inspiring programmes like these catch on and spread around the world. There’s nothing like inspiring someone to act by showing them that it is already being done!

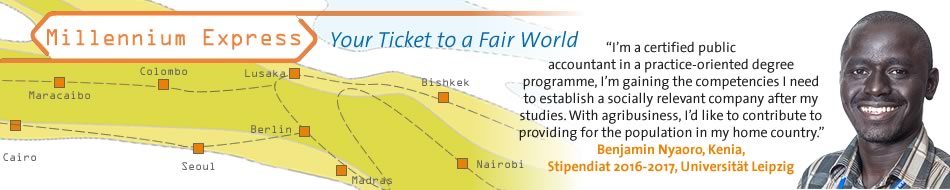

The Millennium Express project is also trying to make a change in the academic community.

I am truly impressed by this unique programme, the diversity of the students and the international and interdisciplinary exchange. The students are genuinely interested in not only understanding but actually tackling the challenging issues of the day. Millennium Express is a wonderful project and it’s a model I believe will catch on.

DAAD’s development-related postgraduate courses also focus on linking academic knowledge and practical experience.

This is a very smart approach. When young professionals from developing countries take the new knowledge and skills acquired in Germany back to their home countries, the distance between knowledge and action is shortened. This makes it a “project of hope”. With more programmes like these and with a new generation of enlightened students we can finally move toward establishing global ecological balance. We could eliminate material and spiritual poverty and contribute to lasting peace and justice in the world.